Jason Scott has spent much of his life making sure digital history doesn’t disappear. As an archivist at the Internet Archive and the force behind textfiles.com, he’s preserved thousands of forgotten documents, games, bulletin boards and other artifacts of online life.

He’s also a filmmaker, best known for BBS: The Documentary (2005) and Get Lamp (2010), the latter a documentary about text adventures and the people who made and played them.

This oral history traces a conversation about Interactive Fiction – especially Zork (1977), Infocom, and the making of Get Lamp (2010). It’s not a biography, and it doesn’t follow a strict structure. But across the reflections and memories, there’s a clear thread: how a genre helped shape a life, and how that life turned to preserving the genre in return.

The story unfolds in Jason’s voice. It’s been arranged to follow a rough chronology, but the tone, pace and perspective are his. That’s part of the value – how he tells it is as revealing as what he says.

This isn’t a definitive history of Zork or Infocom. It’s one person’s memory, but it’s also a document of record. The kind of testimony that might help future readers understand not just what these games were, but why they mattered at the time, and why they still matter now.

Discovering text adventures

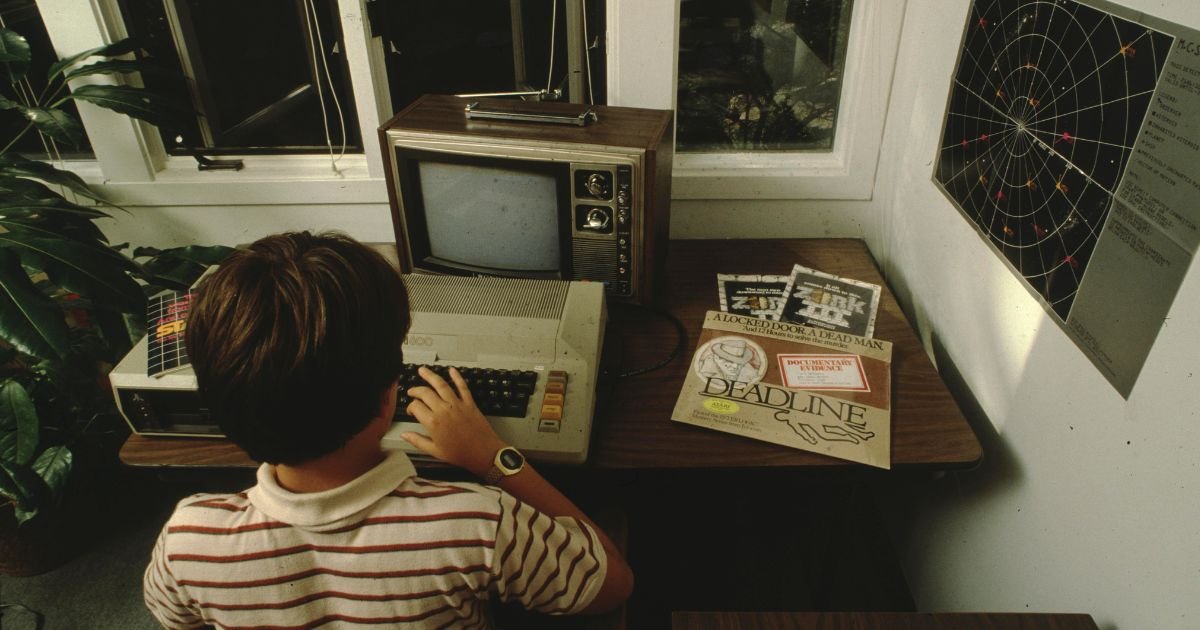

Before Jason Scott preserved videogames, he was a kid discovering them alongside everyone else – he was a player.

I first became aware there were adventure games in 1980. My father would take me to work with him at the IBM Thomas J. Watson Research Center, which is a beautiful Eero Saarinen building in upstate New York.

He had work to do, so he’d set me up on these massive 3279 terminals that looked like they were from space. He knew about the secret games menu, so I’d go there and find a colour list of software – Hunt the Wumpus (1973), stuff like that. And then there was one that said Adventure (1976).

If you’re going in cold and you’re 10 years old, the magic trick is like the Mechanical Turk. It’s very alluring and very powerful to have a prompt that just says “What do you want to do?” The amount of preparation creators William Crowther and Don Woods put in was enough that you really thought the computer was writing it as you were talking to it, especially the first few times.

The first time you find the key, you think, “Oh, this is a key. I wonder what this is for.” And then you find the grate. That’s how you get into the actual cave.

The game was built out of caver’s language at first – Crowther’s background. Then the game was taken over by Don Woods, someone coming from a different direction: Dungeons & Dragons (1974), primarily, or Lord of the Rings (1955). Fantasy layered onto topography.

And I’m playing Adventure and I just think that this is the most magical, great thing ever. Now, Adventure stops everything for about a week in computers. I have multiple citations from people, including the MIT guys, that when they interacted with Adventure, they were like, “OK. Stop everything.” You know, it’d be like if Grand Theft Auto V (2013) just dropped now, and we've never had one through four, right? It would just be like, “Oh my god, what's happening?” Or Red Dead Redemption (2010) – “This is way too big, this is so deep, this has so much going on.”

After Adventure, I played some of the Scott Adams games. I had them for the Atari 800 – I think it was Haunted Mansion (1980) – and then I played Zork II, because it was at a good price on the PC. My father only let me play Adventure a little bit, but Zork II was in the house. I didn’t get very far. I wasn’t very good. But the combination of that IBM 80-column screen, white text on blue, and the fact that it understood full sentences – “Pick up the keys,” “Use the keys on the door” – that really struck me.

There were several ways to deal with the puzzles. Like the dragon, you could hit it with the sword and leave, and it would follow you. You could take it to an ice room where it sees its reflection, breathes on it, and gets killed. It really made you feel like you were dealing with an intelligent computer.

My cousins and I actually managed to solve Adventure, which we thought was pretty amazing.

Now, I didn’t really play that many of them. I had short, intense experiences with the commercial ones – Infocom, Scott Adams… and then I tried to make one.

I tried to make a few. I was terrible.

Part of the problem was, I couldn’t get over the hump. I was trying to do things like: there’s a field, and you set off a grenade. I wanted it so that, if you dropped the grenade and ran, other parts of the map would say, “There’s a distant explosion.” But I didn’t have the coding chops. I got it to work, but it took days and piles of work.

After that, in my teenage years, I got heavily invested in a MUD/MUSH called TinyTIM – it’s still up. I patched holes, added stuff.

So, I dabbled about as much as anyone else had. The same way a kid remembers a couple arcade machines or a family trip to the arcade – later you find yourself in your 30s or 40s, tracking down the people who made and sold those games.

Dawn of the Underground Empire

While Scott was playing text adventures at home, a group of MIT programmers were busy redefining the form.

The Infocom guys were all working at the MIT AI Lab in the 1970s. The lab had been founded by people trying to explore advanced concepts. They were using LISP [a powerful, symbolic programming language widely used in artificial intelligence research] and thinking in terms of modularity. They played Adventure. They solved it. Some of them even looked at the source code – trying to figure out how to get that last point.

There was this thing where you’d get 398 out of 400 points, and the last two were really unintuitive. Thankfully, that idea didn’t catch on. Nowadays, we have achievements. But that was kind of the first version of that idea – do this obscure thing, and you’ll get the last point.

So, they thought, “That’s pretty good, but it’s not that complicated. Why don’t we try doing our own?”

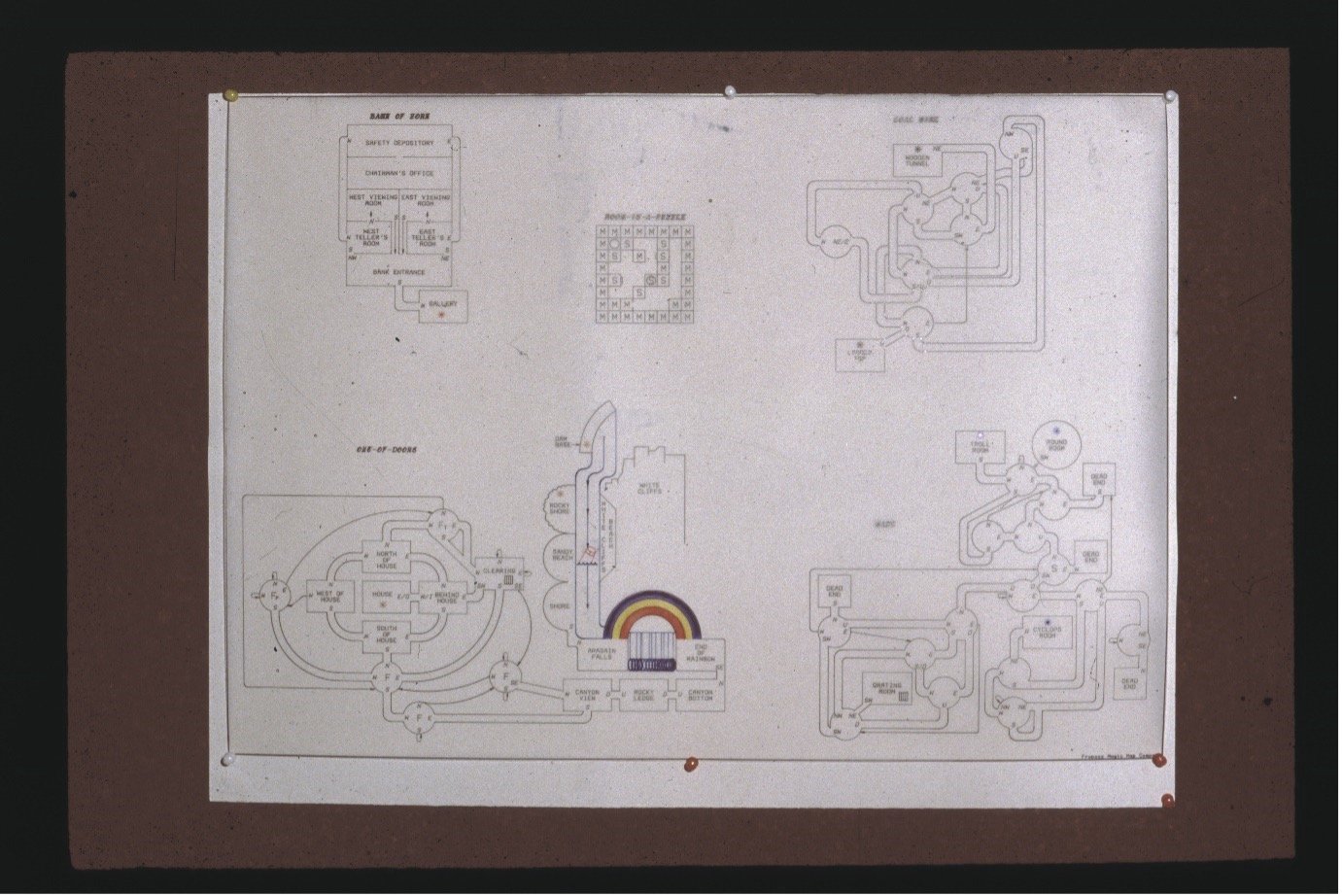

Marc Blank, Tim Anderson, Dave Lebling and Bruce Daniels started hacking together their own system. They wanted something that could understand full sentences. They expanded the map. Over time, they just kept glomming stuff onto it like meatballs. Zork became this crazy, layered mess. But a brilliant mess.

If you look at it critically, it’s even more of a jumble than Adventure. Adventure is caves, then a few non-cave-like things. Zork is architecture, dams, Greek myths, weird characters – just everything thrown in. Over the course of a year or two, they kept adding and adding.

They ended up with a game called Dungeon. It was a monster. I think it took up a full megabyte of memory, which was enormous at the time.

And then they thought: “Let’s start a company.” These were just graduate students. That’s why it was called Infocom – because they literally didn’t know what it was going to be.

From the beginning, they were thinking they might do business software. But to get some money, they decided to package Dungeon for home computers. They renamed it Zork and broke it into pieces that would actually fit on the machines of the time. That’s how we got Zork I, Zork II and Zork III.

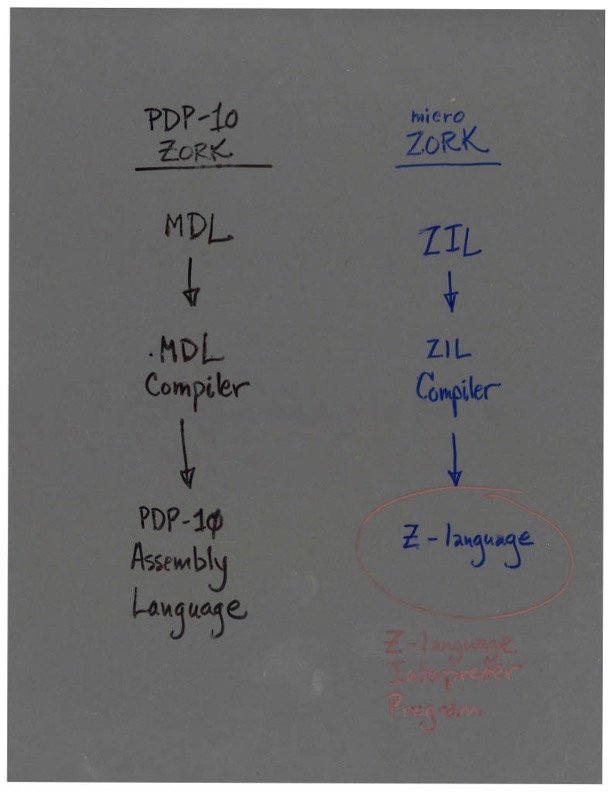

The real magic, though, was the Z-machine.

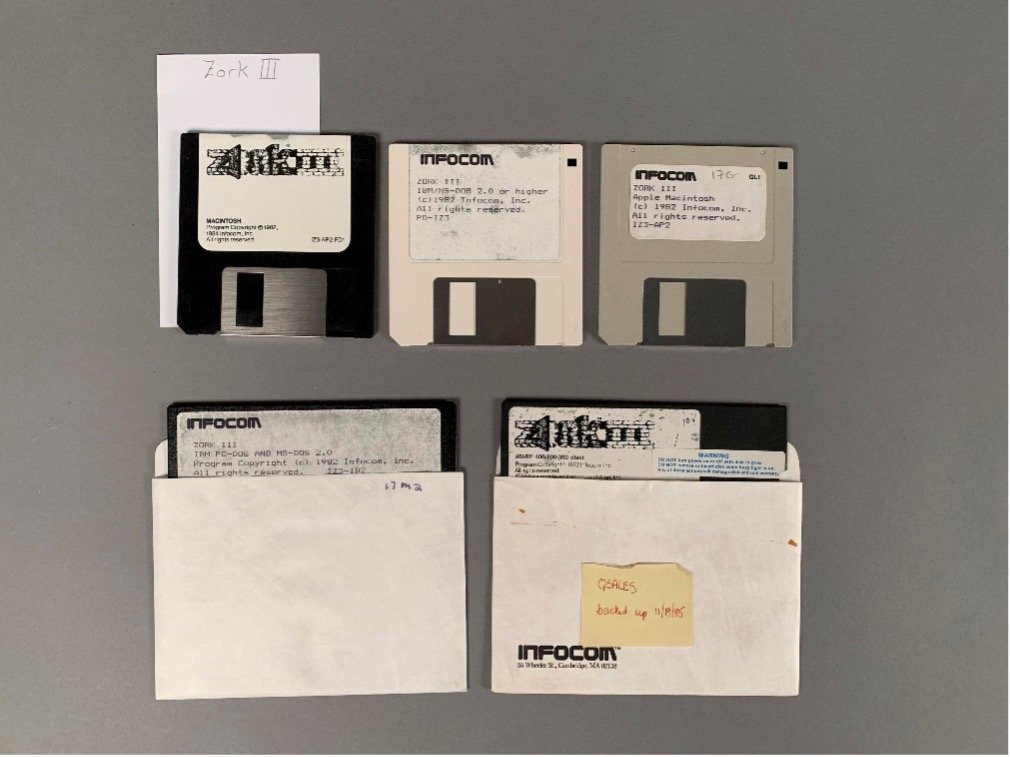

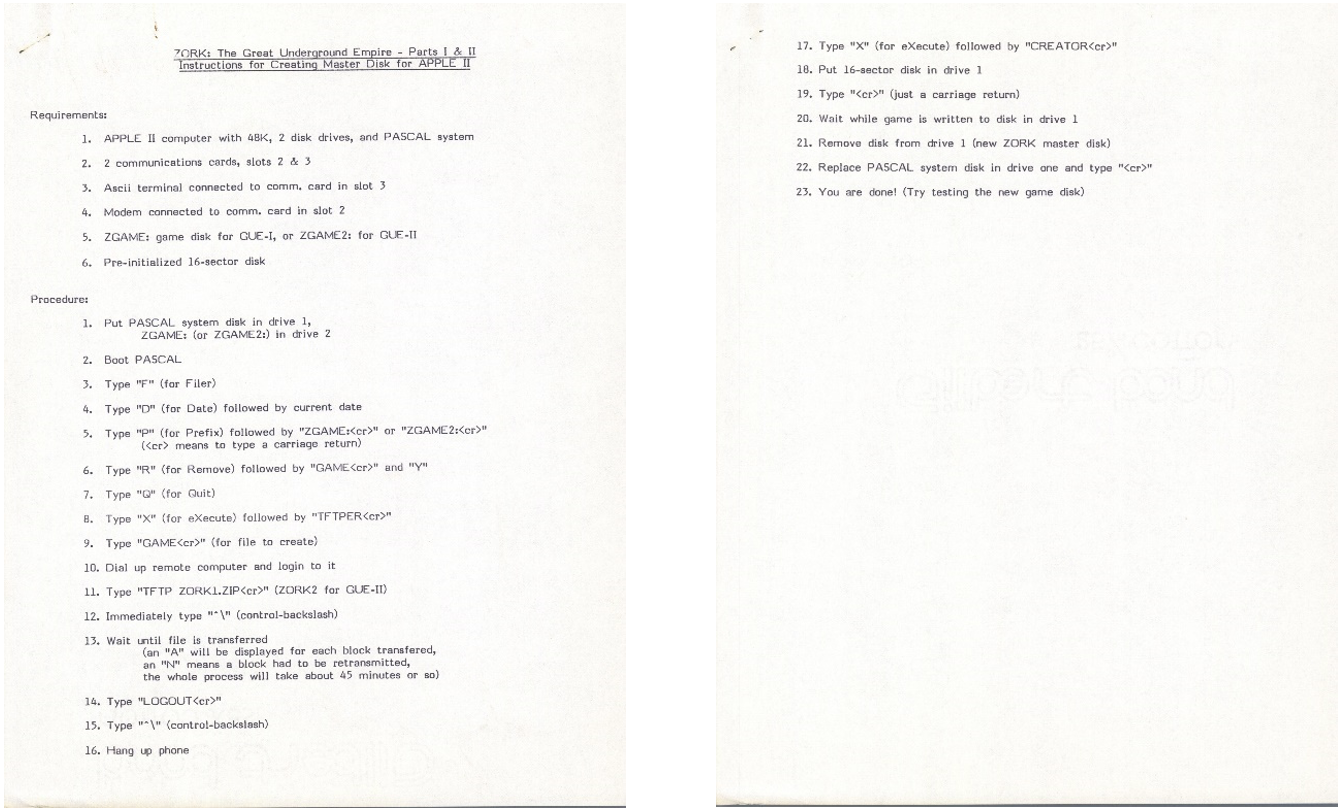

They made something called ZIL – the Zork Implementation Language. That let them write the game once, and then run it anywhere. All the game logic stayed in this portable “story file”. They just had to write a new interpreter for each computer system. Apple, Atari, Commodore, PC, TRS-80 – you name it.

So suddenly, these guys weren’t just making cool text adventures. They were creating a portable storytelling format that could move across platforms seamlessly. And that was a huge part of Infocom’s early success. You could buy a game and know it would work on your weird home computer – and that was rare back then.

Infocom kind of accidentally became a hit factory. People were buying these games at launch. They weren’t just successful – they were a reason to buy a home computer. That’s how strong the brand was.

The Zork Users Group, ‘Feelies’ and the business of fandom

Infocom didn’t just make games – they made culture. And their branding was a major factor in their success.

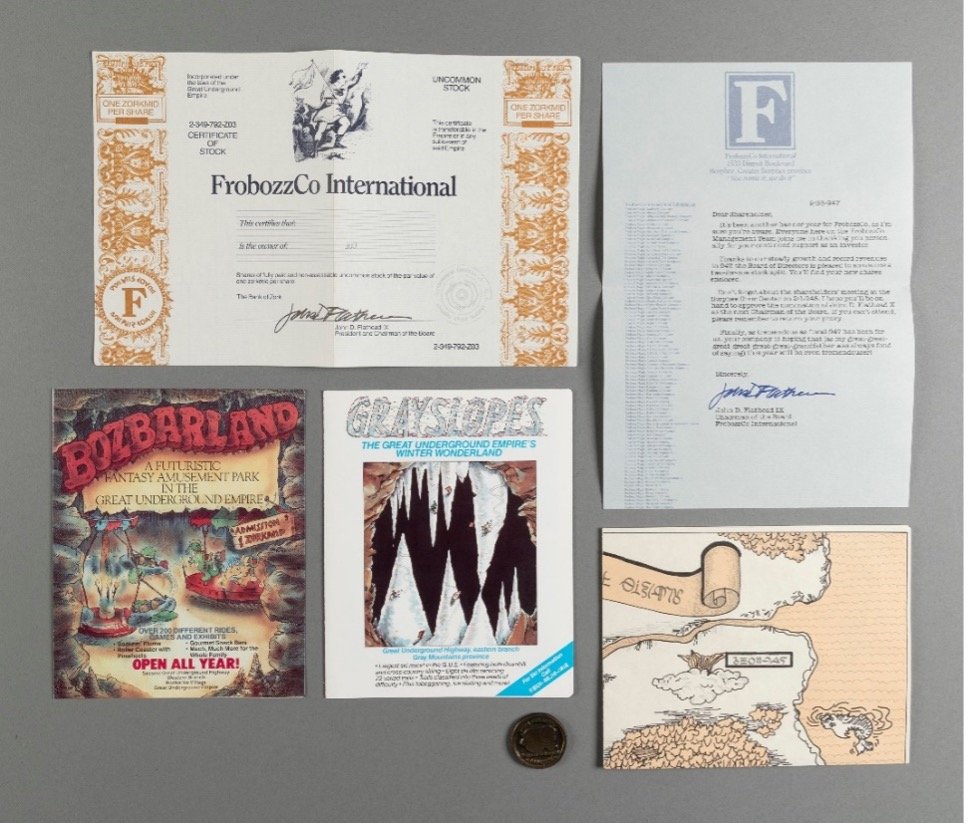

Mike Dornbrook did a lot of work with the Zork Users Group. And it does feel like a proto-internet fandom. But I’ll say this: everything the Zork Users Group did, you can trace back to earlier fandoms. Music fandom in the ’50s. Sci-fi fandom in the ’30s and ’60s. NASA fandom during the Space Race. It’s the same patterns repeating in a new medium.

It just happened that, when Mike came along, his moment was computer games. He jumped in at the right time, saw a need and filled it. And the need was strong enough that even Infocom eventually said, “You know what? We should just buy this whole operation.” That almost never happens.

Calling him a “marketer” is reductive. The real heroes behind Infocom’s visual identity were Giordani and Russell – they came up with the names like Enchanter, Spellbreaker, Deadline. They created the imagery. But Mike’s the one who said, “We need to hire someone like this.” And then he found them.

He was involved at every level. For instance, when they shifted from those elaborate, beautiful packages to the gray boxes – it was to survive in a changing retail world while keeping a little bit of that original magic. That was Mike’s influence.

He also invented Invisiclues. That was his idea – the hint books with invisible ink. He came up with Zorkmids, the fake currency. He just kept identifying opportunities – things that would make the player experience more memorable and more profitable. That was all Mike.

There’s this hilarious story about Spellbreaker. So, the trilogy was Enchanter, Sorcerer, and then the third was supposed to be called Mage. Mike didn’t like the name. He said, “Nobody knows what a mage is. It’s too obscure.” He pushed for a different title.

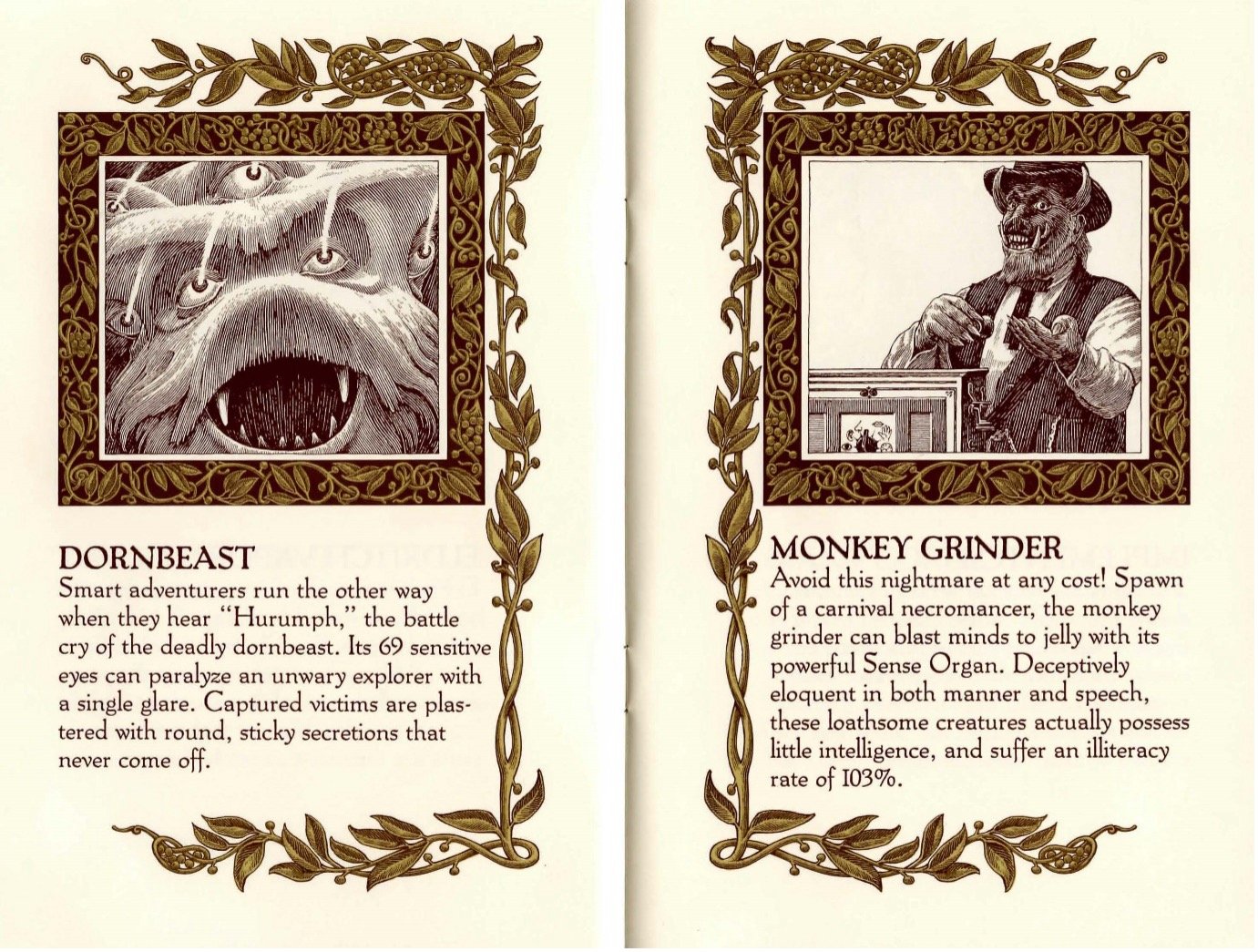

They renamed it Spellbreaker, which Giordani and Russell came up with – and it was a great name. But Dave Lebling, who wrote the game, wasn’t thrilled about being overruled. So, he put a little Easter egg in the game. One out of every ten times you start it, it calls itself Mage instead of Spellbreaker. Just randomly.

Lebling also added a creature called the “Dornbeast.” A kind of in-joke aimed at Mike. Mike’s trying to make the company succeed, get the name out there. And Dave’s like, “Fine, but I’m putting Mage in there anyway.”

But that’s also what’s beautiful about all this. These weren’t giant corporate machines. These were small teams of passionate people, with egos and jokes and grudges. You can feel it in the games.

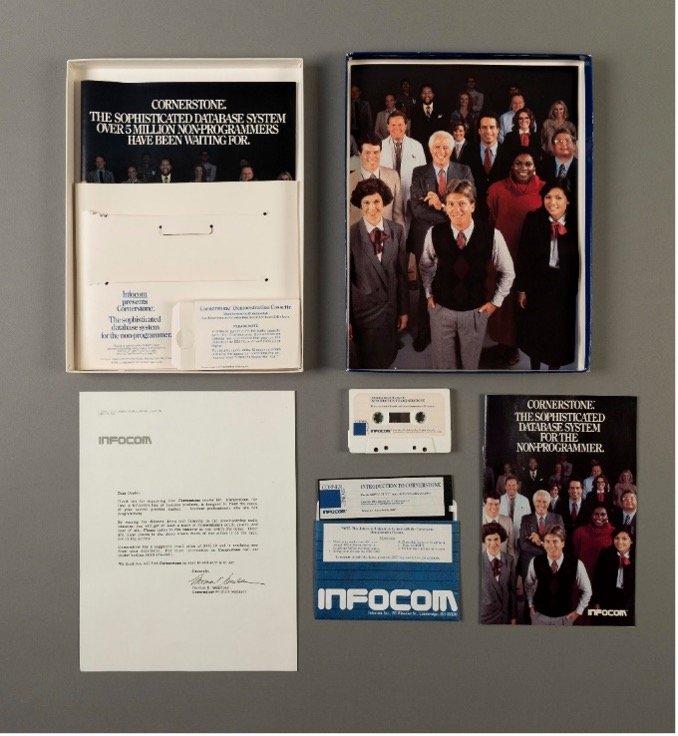

Culture, collapse and Cornerstone

Infocom made its name through games – but its founders never saw that as the end goal.

So, you had all these young people working on wild, creative stuff, and at the same time, they were also developing this business software called Cornerstone. It was supposed to be a revolutionary database – a full-sentence parser system where you could interact with your data like you were talking to a person.

It was going to be the database tool for the next generation. But it took a long time to build, and while they were waiting for it to launch, they kept growing. They bet the farm on it. They took on debt. They believed Cornerstone would make Infocom a unicorn – a company as big and important as Lotus or IBM. But it didn’t work out. And because of that, they had to sell.

They ended up getting bought out. But buying Infocom was like buying the best-run record store in 1991 – just as the music industry was about to change forever.The computer game market was moving on. Infocom was starting to dabble in graphics. Even internally, they were shifting toward other kinds of games. If they’d kept going, they probably would’ve ended up making videogames or even movies. But the timing didn’t work out. They bet everything on Cornerstone, and it just didn’t land.

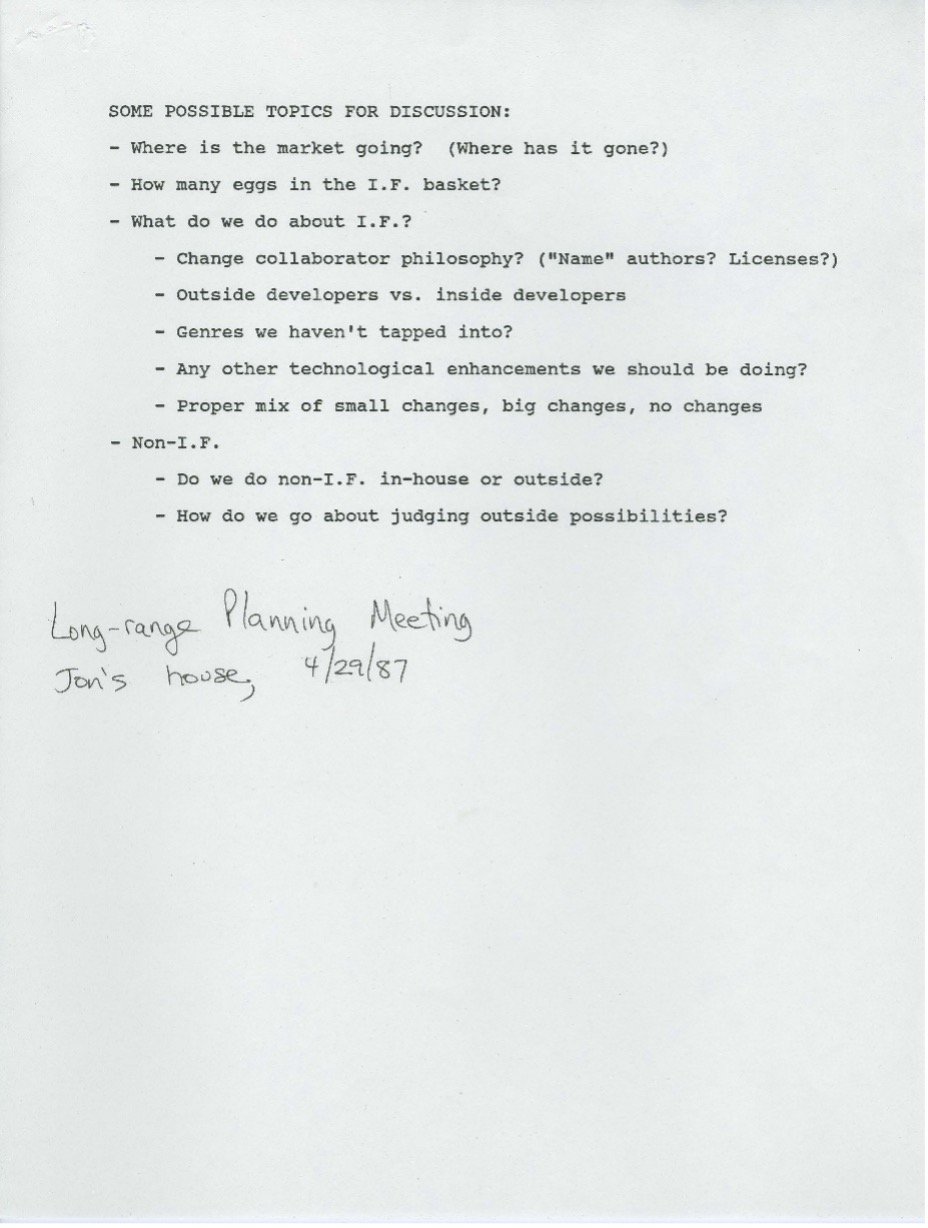

I found that out when I was interviewing Steve Meretzky. He kept everything – every notebook, every piece of paper. His archive includes memos, party invites, design docs, internal arguments. It gives you this rich view of the company – especially from 1980 through the buyout.

You can see them wrestling with direction: “Is this literature?” “Are these games or books?” They were tired of making Zork. Internally, they didn’t want to keep doing it.

You can have the best people, the best ideas, and still get wiped out by a market shift. These products are seen as so fungible – so replaceable. It's not like, say, golf courses, where if someone wants to shut one down, it’s a whole thing.

Games? They can disappear overnight.

Meretzky, though… the man loves the dynamism of creating and playing games more than anyone I’ve known. Part of that is this incredible lack of sentimentality. He doesn’t want to keep making Planetfall or whatever, because there’s no market for it. He’s not like, “Oh, we need another Planetfall.” So as a result, he makes mobile games and works with mobile companies, because that’s what he’s going to do. And Marc Blank moves on to working for Google. Mike and Muffy Berlyn made Bubsy, Toys in the Hood, and a whole series of other games. They just followed the market. I respect that. They weren’t like, “We’re only going to make text adventures because that’s the true genre.” No, they looked at what the industry was doing and adapted.

That’s something people don’t always appreciate. A lot of fans have this purist attitude. They think, “If we’d just given Infocom another million dollars, they could’ve saved the medium.” But that’s not how any of this works. Most people don’t want to read. That’s just the reality.

It’s not about time or money – it’s about audience. If the audience isn’t there, there’s no path forward. It doesn’t matter how brilliant the idea is.

At one point in the 1990s, Mike Berlyn and Blank got back together to make Zork: The Undiscovered Underground (1997), a very light, small Zork game. They worked with one of the newer interactive fiction people and built it mostly by dictation. Just ideas phoned in. The kid would write it up, send it back. That was the process.

And I think that’s about the best you can hope for. Get these two guys who don’t want to crunch code, so they just are able to spend two or three weeks talking into a phone. A kid scribbles down what they’re coming up with and puts it together into a game. And then whenever they find gaps, they call them up and say, “Here’s fifteen situations, what do they do?”

And they come up with it, and that’s it.

There’s this belief that a genre has to survive to be valid. It doesn’t.

There are some things that are timeless.

‘It is pitch black’: making Get Lamp

By the time Scott began work on his documentary Get Lamp, interactive fiction was already a fading art form. What began as a tribute became something more: a race to preserve voices, capture history and honour a community before it slipped away.

When I started working on Get Lamp, I was living in Boston. That helped – a lot of the Infocom people were still in the area. MIT was still there. Nick Montfort was there – he was the academic I connected with. He’d written a really great book about interactive fiction called Twisty Little Passages.

Nick had this photographic memory. We’d be in interviews and he’d say, “You never asked him about ‘blank’.” And I’d go, “How the fuck did you remember that?” But he was sharp. He could keep the whole concept in his head.

I also hung out in IFmud. That was their community space – people like Zarif, Robb Sherwin, others running adventure game stuff.

I interviewed a broad swath of Infocom implementors, plus some marketing and editorial folks. Not everyone agreed to be interviewed. Some people thought I was out to do a hit piece. I wasn’t. I just couldn’t get across what I was trying to make.

But when people did sit down, the material was gold. These weren’t just interviews – they were records. People remembered stuff no one else knew.

That’s what I’d already learned from the BBS documentary. I interviewed the guy who made the very first BBS. Went to Chicago, talked to him for five hours. Talked to the guy who co-created it. Talked to the guy who was inspired by them. And more people who were there at the time.

Their opinions didn’t always match, but they were aligned on the big things. And the only way to preserve that knowledge was to talk to them. Film them. Record what they remembered. Whether it’s a SysOp, a BBS software author or someone like Dornbrook – you’re getting stories that don’t exist anywhere else.

I’ve found it rewarding, over and over. I gather materials. I talk to people. And someone, someday, is going to build a much richer, more accurate narrative out of all of it.

And yeah, it’ll probably be a language model. We’re still in the 8-bit phase of those systems. But one day you’ll say, “Here’s the body of work. Only use this. Don’t pull anything else in.” And it’ll start churning through gigabytes of material and generate five possible narratives.

But it won’t work unless the material is there. Preserved, digitised, accessible.

Players, puzzles and the legacy of Interactive Fiction

Even if the golden age of interactive fiction is behind us, its DNA lives on – in puzzles, indie games and the people still drawn to writing, exploring and preserving these digital spaces.

To me, the genre is still really interesting. Still exciting. Like literature is.

But if you’re making a new text adventure today, your audience is probably people aged fifty to seventy. And even then, not many of them want to spend hours typing commands. But it’s possible. You could still hit something big.

Sometimes it happens. Someone makes something like Balatro (2024) or Animal Well (2024) – a weird, beautiful, solo project – and it blows up.

Right now, I think the closest thing in spirit is Blue Prince (2025). I played it for a day and I hated it – too much randomness. But once you get past that? Puzzle after puzzle. There’s math, logic. It demands you write things down. People are keeping notebooks next to their computers just to solve it.

All the attributes of a text adventure are there. You’re moving through space. You’re exploring. You’re interacting. You’re writing things down. It’s just a different interface. You’re not typing ‘GO NORTH’ anymore – but the bones are the same. I don’t know if anyone from Infocom would look at Blue Prince and say, “Yeah, that’s what we were aiming for.” But the lineage is real.

People still argue about what defines a text adventure. Whether it’s more about the writing or the puzzles. It’s like asking, how much of Doom (1993) is about arcade shooting, and how much is about exploring? If you talk to John Romero, he’ll say they wanted the interface to disappear. They wanted you to feel like you were the protagonist, moving through these strange spaces.

Same with interactive fiction. Some people saw it as literature. You’ve got games like Photopia by Adam Cadre (1998) – emotional short stories, no real puzzles, mostly on rails, but deeply affecting. That’s literature. On the other end, you’ve got the hardcore puzzle games from the IF Competition. Both are valid.

If you stop worrying about making a fortune, it’s still a vibrant space. People are making these games. People are playing them. It’s happening.

The real challenge is: Can you make something that pulls people in – even if they don’t know what kind of game it is? That’s the magic trick.