Creating an outstanding production learning resource

Subject: Media

Year levels: 9 – 12

This resource has been written for ACMI by expert Media teacher Victoria Giummarra.

Getting started

So, you are planning to make a production! This step-by-step guide will help make this the highlight of your studies in Media. Creating a unique and engaging work of art is a daunting task, but planning, attention to detail and a great idea will lead to a successful outcome.

Complement this resource with a visit to ACMI's centrepiece exhibition The Story of the Moving Image, which offers a wealth of insights and examples to fuel your creative learning. Download the worksheet below to guide your visit.

Where to begin?

Think of your media production as a story, created for a particular audience, and told with the use of technologies. When making a media production, there are some key considerations to work through:

What media form will you work in? While video is the most popular form for Media students to work in, it’s not the only option. Media productions can also be created in photography, print, audio and digital formats. If a certain media form isn’t dictated by the set task, consider what interests you, your previous experience and available equipment and technologies.

What genre or style will the production be? Once you’ve chosen your media form, categorising your production idea as a particular genre or identifying additional aspects of its style (e.g. period piece, non-linear narrative, or manga) will help you establish the conventions your production may draw on and include.

What is the narrative? Media productions, regardless of the form you choose to work in, have a focus on telling stories. These may be fictional or non-fictional, but some sort of ‘chain of events’ is needed to craft a story that feels as if it goes somewhere. As the creator, you shape which events we see and in what order they occur.

Who are the audience? All media productions are created for an audience. You may have heard the term ‘target audience’ before. Like a target, the group you plan to make your production for should be small and specific. While it’s great to hope everyone from ages 8-80 will enjoy your production, you’ll likely make more appropriate choices if you appeal to a smaller group whose tastes you can identify clearly. This could be your class, your family, teenagers your age, or fans of a particular genre.

Once you can answer these questions, you’re off to a great start!

Working through the production process

After you’ve made some initial decisions about the basics, the next step is to get started. This is best done in a logical and structured way, where each task you complete moves you towards creating a skilful final product.

The VCAA VCE Media Study Design outlines a 5-stage production process that reflects how professional media products are made in the industry. These stages are:

- Development

- Pre-production

- Production

- Post-production

- Distribution

Looking more specifically at each of the 5 stages, let’s consider some of the tasks to undertake to help you plan and deliver an outstanding production.

Development

Development involves exploring the ideas, intentions, narrative and audience of a production. In this stage, media practitioners may research other media products, analysing codes and conventions, narrative, genre or style and may consider the societal context of a product. Media practitioners may investigate equipment, materials and technologies in a range of media forms relevant to their audience and intention. They may perform experiments using materials, equipment and technologies to develop their skills.

- VCAA VCE Media Study Design 2024-2028

This stage is all about generating ideas. You need to spend time researching a media form and its audience, keeping in mind your desired genre and style, and learning from the work of other creators. You can also look into what inspires you and maybe consider narrative possibilities that are different from the ‘norm’.

Some suggested tasks to undertake in this stage are:

Become an expert: Research the media form, genre and style you have chosen to work in to help you better understand what makes a skilful and engaging production. Look at great examples of other practitioners' work – including professional, indie and student creators.

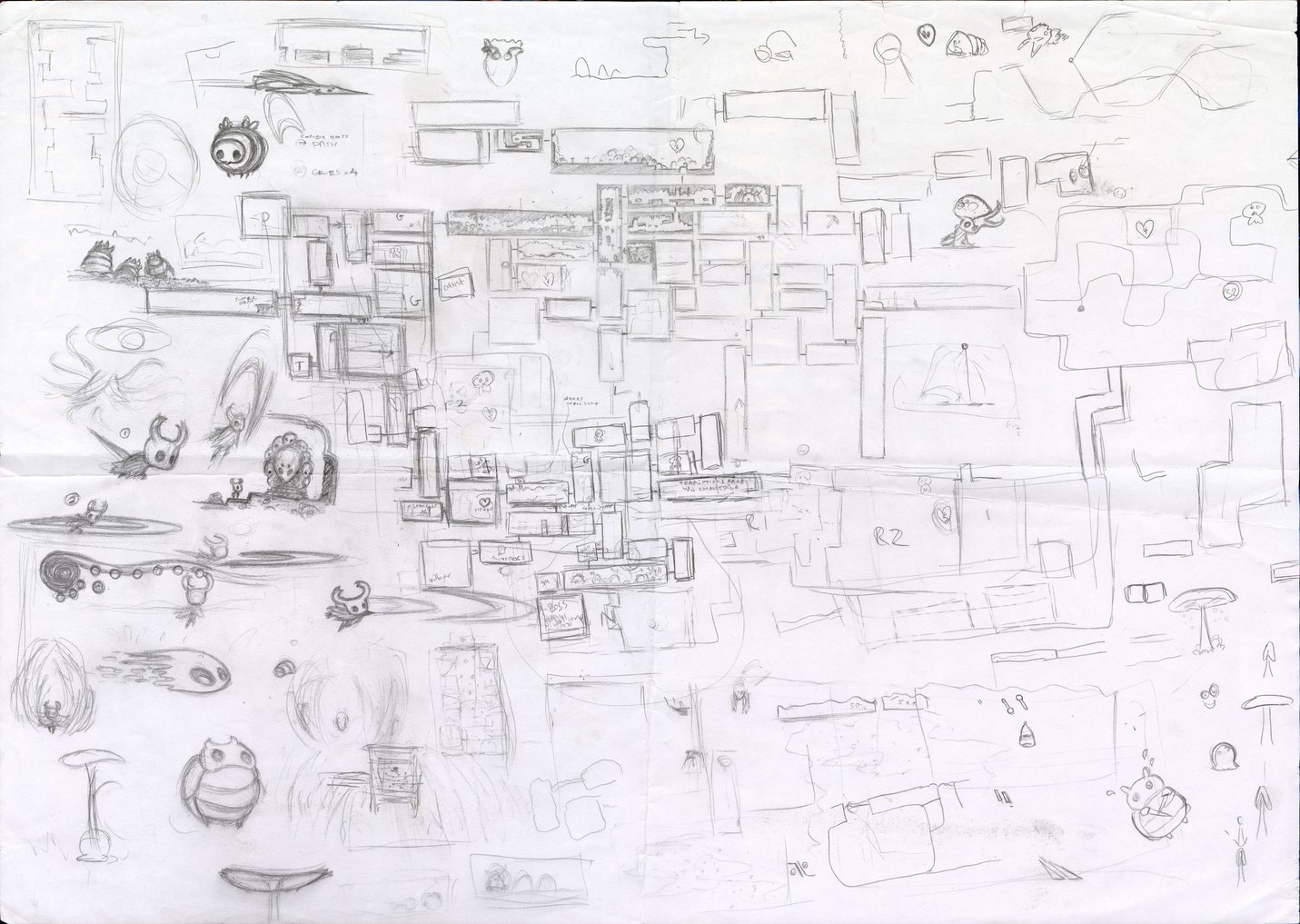

Develop a ‘look’: While a clear or final story idea may still be elusive at this point in your project, working with pictures and the appealing visuals you’d like to achieve can be a good place to start. This will also help you decide how you want to apply the technical elements, including codes like camera, lighting, mise en scene or costume in your production. Creating a moodboard (the example here is specifically focused on developing a photographic product) or making a Pinterest page to collate images digitally will give you something to come back to and draw on down the track.

Brainstorm story ideas: Explore some of the narrative prompts you can find on websites like this one and this one, which even arranges ideas into genres. While based around making a short film, many of the ideas are adaptable to other mediums. Remember – your first idea probably isn’t your best one, so dig deep and try to move beyond the conventional and towards something more original.

Consider the possibilities but be realistic: It’s important to remember you need to create the production you plan, so you must be realistic about your ideas. This may include the design of your product, your cast size, locations and any planned special effects. Before you discount any ideas, be sure to investigate your options.

Chart your ideas and arrange your narrative: Once you have some narrative ideas, find ways to document and develop them. A hand-drawn brainstorm or digital mindmap can help here, but you can also make use of more formal media production tools. Here are some which can be helpful for developing the 3 act structure of a short film or a character’s arc or exploring the different structures of video game narratives. The structure of a media narrative is often driven by expectations around the genre and form. It’s worth researching what’s typical for the type of production you are pursuing.

Most satisfying stories, regardless of the form they are told in, have a beginning, a middle and an end that allow the story and character arcs to build and develop throughout the duration of the narrative. Within this there will be certain stages or events that occur such as exposition (set up), conflict, climax and resolution.

Some questions to ask to expand your thinking about your story are:

- What is the ‘world’ of the story? Consider context and setting.

- What narrative structure will you follow?

- Will the story unfold in linear or non-linear order?

- Who are the characters? What will make them memorable and engaging?

- What is the problem/tension and will this be resolved?

- How can you create an enticing opening to grab your audience's attention?

Pre-production

Pre-production planning considers the concept, audience, intention, narrative and context of a media product. Pre-production involves planning a narrative, including how it will engage, be consumed and read by an audience. Media codes and conventions, genre and style are considered in the construction of the narrative. Documentation and planning may take visual and written forms, such as production notes or storyboards. Media practitioners may undertake technical tests and experiments prior to production, reflecting on their success or failure. Equipment, technologies and materials to be used in the production are documented. Media practitioners plan how the product will be distributed to an audience and the context in which it will be consumed.

- VCAA VCE Media Study Design 2024-2028

In pre-production, you need to ‘lock in’ your intention, audience, genre and style, as these impact the rest of the choices you make, going forward. In this stage, you begin to see your narrative come to life on paper (or its digital equivalent), as you thoroughly document your ideas using written and visual planning.

Stating your intention: Consider the following questions –

- What is the purpose of the production? (e.g. inform my audience about sport of pickleball, including its rules, local leagues/tournaments, plus its social and health benefits)

- How will it impact audiences? (e.g. help them understand more about the sport through both voiceover commentary and interview footage, in a manner that is as relaxed and enjoyable as the sport itself)

- What outcome will it have? (e.g. develop greater appreciation for pickleball and encourage the audience to give the sport a try)

Knowing your audience: Develop an audience statement by considering –

- Who is the target group for the production? This could include an age range, likes/dislike etc. (e.g. people between the ages of 18-22 who live in inner Melbourne and are studying and working but not currently participating in team sport)

- What attitudes/knowledge/expectations do they have? This will help you explore what your audience may bring to their experience of your production (e.g. they believe engaging in sport takes up a lot of time and effort but may not know pickleball can be played in relaxed settings and by those with no expertise and average physical fitness)

- Finally, how and where will the production reach the intended audience? Consider the context your work will be made for and how it will be best appreciated. This could be a big screen/cinema, in print form in a zine shop, as a hung exhibition in a particular type of gallery, or streamed via an online platform to interested individuals.

Planning in writing: Scripts and treatments are common ways to document a media production’s content. There are some expected ways to format these, so seek out examples (such as this film script or this useful ACMI Film it: Screenwriting guide) relevant to the media form you have chosen.

Planning with visuals: This also allows you to visualise how the production might be framed and shot, or perhaps what colour palette suits your mise en scene. When completed thoughtfully, visual planning can help ideas come to life, as you can see in this video.

Common forms of visual planning for different media forms include storyboards for productions with moving images, and sketches or digital mock-ups for productions with still images or layouts. (You can read about someone who works in magazine design and the tools they use here).

If you’re planning an audio production, you could also use a visual tool such as a broadcast clock to show how the time will be divided up to cover the content. You can find examples of these types of planning tools online.

Other pre-production tasks may include:

- model building, character design

- casting, location scouting, wardrobe tasks such as sourcing costumes

- equipment booking or hire

- scheduling production tasks and call sheets for actors and crew

- determining and assigning necessary production crew roles

If you’re a VCE Media Unit 3/4 student, refer to the list provided by VCAA in the School Based Assessment advice (this is produced for each new year) to double-check all the inclusions necessary in your pre-production planning.

Production

Production is when a product is captured or recorded. Production may be a collaborative process involving a number of people with specific roles or it may be an individual process. Reflection and evaluation of the production can occur through written documentation, oral feedback and visual feedback.

- VCAA VCE Media Study Design 2024-2028

So, after a whole lot of hard work and great planning, the time to make your production finally arrives. This ‘making’ stage is fun and hands-on, but can also be less predictable. If you are making a film, it's likely you'll be dealing with actors or talent, crew, equipment, location and possibly even the weather! Other kinds of production will require different forms of problem-solving and having to learn on-the-job.

You’ll need to consider production challenges during the pre-production stage (and have a few contingency plans in place) if you want to ensure a smooth-running production stage.

Here are some tips:

Equipment: The production you can make is somewhat dependent on the equipment you can access. This may come from a range of sources, such as school, family, friends or hire. It’s important to remember though, making a great production is not always about what you have, but what you do with it. Can you make a great production on a smart phone camera? Sure. The trick is to know the capabilities and limitations of what your equipment can do and work accordingly. You can find some great tips online for homemade budget equipment if you’re willing to do some DIY. Test out all equipment and software before you actually need to use it. This is not only to check it works, but to ensure it can do what you are aiming for.

Locations: Use your contacts to find great locations you can access for free or at a low cost. For example, you could use an underground carpark at a parent’s workplace, a café or doctor’s surgery run by a relative, a retro kitchen at grandma’s house etc. This may mean you can avoid having to enter into negotiations or formal location agreements. Think flexibly here too. If you can’t access your locations at night, can you shoot during the day and tint this later?

If you’re creating an animation, you might be constructing locations and sets yourself, either digitally or physically. Think about the look and style you’d like to have and keep scale in mind. Building or creating these first will help you keep other items (such as characters) in proportion.

Find out more about the Memoir of a Snail animation production process in this behind-the-scenes video.

Finding and directing actors/talent: If you want your production to be believable and professional, then you’re probably going to need to find some age-appropriate and suitable looking actors/talent who are comfortable in front of a lens and/or microphone.

Your family members and friends are great assets here, as they will probably be willing to help you out and are less likely to let you down. If you’re looking for ‘experience’, approach the Drama students at your school or seek out actors from a local children’s acting school or community theatre company. Doing some initial audio demos or filmed screen tests can help less-experienced actors hear/see their work and consider how they might adjust their performance.

As the director of your production, you will need to be able to convey your ‘vision’ to others working on your production through clear instructions. Sharing your written and visual planning can help here. In the production stage, you need to be organised and able to tell cast and crew exactly what you want from them. Communicating the objective of each character and the purpose of each scene will help ensure everyone is on the same page creatively.

Be friendly but firm as a director – you don’t want to waste anyone’s time. Be organised, stick to call times (realise that everything will probably take much longer than you think, so factor this into your scheduling). Check back what you’re capturing while still on location, so you can minimise having to do re-shoots or new takes later.

In the professional world of film and television, having catering on set is a MUST! A few takeaway pizzas or some home-cooked goodies will keep people happy and can mean a lot.

Post-production

During post-production, the production is refined and resolved, considering the intention, audience and planned narrative. Codes and conventions are used to resolve ideas and engage audiences. Specific equipment and technologies are used in editing. Feedback is sought and the creator and participant will reflect upon the product and its relationship to the specified audience and intent.

- VCAA VCE Media Study Design 2024-2028

After completing your production tasks, you are ready to assemble whatever you captured/created into a meaningful and impactful story. The post (meaning ‘after’) production stage is where you will revisit your narrative, intention and audience planning to help you make decisions about what makes it into your final work and what gets left out.

Selecting your tech: The assembling and refining of your production will more than likely involve the use of editing software of some kind. Depending on the media form you are working in, this may be a program like Photoshop or Lightroom (for photography), InDesign (for print), Premiere or Final Cut (for video). There are many great options out there, both paid and free. Use whatever you have access to and be willing to skill-up in knowing how to push it to the max. Online tutorials can help you here – just search up what you need to know and the internet will provide!

Editing: Editing your film production involves cutting and arranging of any vision and/or sound. In addition, editing may also include adding enhancements to your work. When undertaking this task, you will start to see your ideas from your planning and your production work combine and come to life, which is exciting! If you’re completely new to editing and happen to be working in video, this ACMI Film it: Editing resource can help teach you the basics. Editing on professional media productions is usually undertaken by a specialist and it’s definitely something you get better at the more you do.

When editing a film, consider:

- the ordering of your scenes, shots and story is important – not only does this impact the clarity of your narrative, but also the audience’s reading and engagement with it.

- the opening moment or scene needs to ‘grab’ your audience.

- pacing and rhythm, which are important concepts in editing. Pacing is about the overall speed at which your story unfolds. This may be somewhat dictated by the expectations of the genre you are working in (for example, an action film will be much more fast-paced than a drama). Think of rhythm as the ‘beats and pauses’ in your work. It can be useful to revisit some of your initial inspirations and chart how they use rhythm and pace (e.g. count length of shots and the frequency of cuts, new cells, frames or pages).

Australian film editor, Jill Bilcock explores the power of editing in shaping meaning for audiences and how changes in technology have altered the work she does in this ACMI interview.

Sound: If your production is in an audio-visual media form, sound is an important technical code that can really help with storytelling. Consider the role of both diegetic (existing in the world of the story) and non-diegetic (added in for audience impact) sounds, such as dialogue, effects, music, voiceover/narration. Don’t discount the absence of sound here too – sometimes a well-placed moment of silence can be powerful.

A Foley artist creates and records sound effects for film, TV, or other media during post-production. They use various props and techniques to mimic everyday sounds, like footsteps, door creaks, or rustling clothes. These are then layered into the soundtrack of a production. You can read more about their work and listen to some of the aural magic they create here.

When recording sound like foley or a voiceover use a decent microphone and ensure your environment is free from extraneous noise. Be sure to use headphones when recording sound to ensure you’re getting what you need at an appropriate volume and without any ‘hum’. If you’re new to managing sound, this ACMI Film it: Sound recording resource will provide you with helpful tips. If you haven’t got access to mics, you can also use your smartphone as a recording device. Try a free app such as Voice Record Pro (available here on Apple’s App Store) which can be set to record broadcast quality sound.

If selecting audio tracks like music or effects to use in your production, aim for those that are classified as royalty or copyright free. These are usually free to use (perhaps with a credit) or involve a one-off low cost licence fee. You can find plenty of sites online that offer such audio files.

You can also create your own original audio tracks with the help of musical friends, software loops like those found in programs like Apple’s GarageBand, or by using AI generated music apps.

Enhancements: Colour correction or computer-generated effects may be features built into your editing software. If not, you can find additional specialist programs (such as Adobe AfterEffects) and presets (which are existing effects templates, like those found on websites such as Motion Array) to overlay/apply on your production. As their name suggests, enhancements should be purposefully used to help to make your production, its aesthetics and storytelling better. Don’t think of them as being absolutely necessary or as the ‘fix’ for shoddy production work, such as poorly lit footage. If you’re new to using colour correction tools, you will find this ACMI Film it: Colouring resource useful.

Seeking and giving feedback: As you refine your work in post-production, it’s valuable to seek feedback on your production to make sure it ‘hits the spot’ with your target audience. Initially, you should seek feedback as to whether your production:

- makes its intention clear

- communicates the story

- engages the audience

- is technically sound (e.g. plays/advances/reads as it should and without errors)

Beyond this, it can also be useful to collect feedback about:

- what the audience value in the work (e.g. what makes it special or memorable)

- any areas of concern (e.g. what’s not understood or working presently)

- ideas and suggestions (e.g. what can be added to improve the work)

Your Media classmates, teacher, family and friends are people you could also seek feedback from, but you may like to share your work more broadly with those in a trusted online community. Preparing a survey or form to collect feedback can be really useful (and if you’re doing VCE Media, essential) documentation you can revisit as you work to make changes and refinements.

Distribution

The product is delivered to the specified audience in a planned context and location. At this point, the creator and/or participants will seek feedback for future productions based on audience response and personal reflection.

- VCAA VCE Media Study Design 2024-2028

After a whole lot of hard work and seemingly endless tasks, your production will one day (finally!) be done. It’s a great feeling but the real reward is being able to share your work with an audience.

The viability of the internet as a global streaming platform has definitely re-shaped the media landscape when it comes to distributing a production, both for beginning and experienced creators. For high-budget media productions, marketing is still a key component in ensuring a product is visible and accessible to its potential audience.

Audiences are an essential part of making media. As part of the planning for your production, you specified a context or way your intended audience would ideally receive the work you were making. So, give this a go. If it’s not entirely possible to do as you planned, try to find different ways to share your work with others. Like with all choices you make, the impact and meaning of your production will vary depending on way you choose to share it.

Having a variety of audiences and reception contexts for your production will provide you with valuable insights into how work is best received. These, in addition to all other reflections you have undertaken throughout the production process, will help make you a better creator for next time.

Good luck on your media production journey!